History of Homosexuality in Berlin

How the gay and lesbian scene in Berlin emerged

Back in the 1920s, Berlin had already become a haven and refuge for gays and lesbians from all over the world. There are 170 clubs, bars and pubs for gays and lesbians, and well as riotous nightlife and a gay neighbourhood. But parties aren't the only thing being organised – several political associations are founded in Berlin to fight for equal rights. However, the Nazis' rise to power spells the death knell for this diversity, and it would take several decades for Berlin to return to its status as a global centre for the LGBTI* scene. Learn about how Berlin became a hotspot for gays and lesbians over the course of the 20th century, and how its scene attracted people from all over the world – and continues to do so today.

1897

The Scientific-Humanitarian Committee – the very first gay and lesbian organisation in the world – was founded in Berlin. Its founder is the Jewish doctor Magnus Hirschfeld. His guiding principle: “Justice through science”. His goals: freedom from persecution by the state and religious oppression, the fight for emancipation and social recognition. The Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, remains the most politically influential association with its lobbying activities, its alliances and awareness campaigns, right up until the early 1930s.

1900

One of the first gay venues in Berlin, notorious for frequent raids by the police, had already been open in Jägerstrasse since 1885. In 1900, Magnus Hirschfeld is aware of six pubs known to be venues for gays and lesbians. By 1910 there are twice as many.

Public parks such as Tiergarten, public baths and a range of railway stations traditionally provided places for many homosexual men to meet. These also included public urinals, facetiously known as “Café Achteck” (Octagon) in Berlin due to their shape.

1903

Another homosexual association is founded with an exclusive Union for Male Culture, which called itself the Community of the Unique. Its founder, the publisher and anarchist Adolf Brand, acknowledges the existence of a distinct homoerotic cultural history extending from Ancient Greece through to the present. The “unique” consider themselves to be a cultural avant-garde, and defend their socially privileged status as men – something which did cause some controversy.

The “unique” meet up at the home of the publisher in Berlin-Friedrichshagen. In the 1920s, a series of talks are held in the union's own clubhouse, Marinehaus, at Köllnischer Park.

1905

Starting in 1901, the literary and artistic bohème gather in the Dalbelli trattoria on Schöneberger Ufer, where they hold evening lectures and cabarets. Among others, Peter Hille and Else Lasker-Schüler, Erich Mühsam and John Henri Mackay recite poetry there. This is also where Else Lasker-Schüler makes friends with Magnus Hirschfeld. Mühsam and Mackay start contributing to the “unique” from this point on. The co-owner of the restaurant, Alma Dalbelli, continues running the business as the Como from 1905 on: it was Berlin's very first gay wine bar.

1910

Lesbians generally became involved in bourgeois feminism as a way to assert their interests and to fight for the right to their own careers and independence, as well as the right to political activity and the right to vote. Their ranks include feminists and suffragettes famous across Germany, such as the Berlin-based Helene Lange and Gertrud Bäumer, who live together as a couple.

A number of lesbian women, including Johanna Elberskirchen and Toni Schwabe, take a pro-active stance and fight to become actively involved in the gay movement, arguing in favour of having their say in Magnus Hirschfeld's Scientific-Humanitarian Committee. Their persistence pays off when Toni Schwalbe is elected to the Chairmen's College, the governing body of the committee, in 1910 and Johanna Elberskirchen in 1914.

1919

The Scorpion, the first lesbian novel, is penned by the Berlin author Elisabeth Weihrauch in 1919. Furthermore, the first gay film, entitled Different from the Others (directed by Richard Oswald), is shown in cinemas.

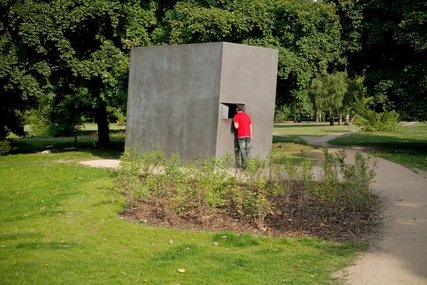

The Institute for Sexology, headed by Magnus Hirschfeld, opens in Berlin's Tiergarten. It is a doctors' clinic and, at the same time, a centre for the gay and lesbian emancipation movement. Congresses and campaigns focussed on sexual reform make it internationally renowned. It proves to be a crowd-puller with its functions to increase public awareness and its museum on the history of sexuality.

The institute stood at the site where the Haus der Kulturen der Welt (House of the Cultures of the World) now stands in Tiergarten. There is a column not far away to commemorate it.

1921

The gay and lesbian movement rapidly gains pace with the Friendship Associations and their local branches all over Germany, which are founded from 1919 on. In 1923, the associations are united under the leadership of the publisher Friedrich Radszuweit in the Association for Human Rights. The same year, he opens the first bookshop for gays and lesbians.

In Berlin, around 40 venues open as meeting places for men – and increasingly for women as well. In 1921, there is an International Travel Guide to promote them – the very first gay and lesbian guide. A number of barkeepers join forces to support the movement.

Magazines for gays and lesbians are available at public kiosks and in the venues: they include Die Freundschaft (Friendship), the Blätter für Menschenrecht (Magazine for Human Rights), Die Freundin (The Girlfriends), Frauenliebe (Women's Love), and Das dritte Geschlecht (The Third Sex) for transvestites and transsexuals.

1922

The competing gay and lesbian associations are united in their fight against Paragraph 175 (which criminalises homosexual acts). The Scientific-Humanitarian Committee had been filing petitions since 1897 calling on the Reichstag to abolish the special law against homosexual men. More than six thousand prominent personalities from the German Empire and, later, the Weimar Republic have signed the petition.

In 1922, the gay and lesbian' associations briefly unite to form an action group to ensure their voices are heard during an upcoming criminal justice reform. The Scientific-Humanitarian Committee drafts an alternative concept that gained much attention, and in 1928, the criminal justice commission responsible decides to reform Paragraph 175. However, the hopes of newly-found freedom are soon dashed by a conservative government that is elected to power.

This means that the Berlin Police Headquarters at Alexanderplatz remains a credible threat of force despite its policy of tolerance towards the gay and lesbian scene. This site is now occupied by the Alexa shopping centre, with its size and colour serving as a reminder of the former red behemoth.

1925

There are now around 80 venues for gays and lesbians in Berlin: beer-soaked dives and distilleries, bourgeois restaurants, wine bars and clubhouses, dance halls and dance palaces, ballrooms and cosmopolitan night-time bars. From 1925 on, large-scale events are held in the ballrooms in Alte Jacobstrasse and Kommandantenstrasse, or in the Nationalhof in Bülowstrasse.

As the manager of the Violetta Ladies' Club, Lotte Halm, along with several hundred of her fellow female members, helps shape major sections of the lesbian movement and entertainment scene from 1926 on. She unites her association with the Monbijou Women's Club in 1928, which also includes transvestites and transsexuals, cooperating with the Association for Human Rights and constantly finding new venues for events.

Numerous hotels and guest houses, beauty and hairdressing salons, tailors and photo studios, doctors and lawyers in private practice, libraries, cigarette and shoe shops, and even a car rental company, a travel agency and a distributor for potency pills advertise in gay and lesbian magazines.

1928

A travel guide for lesbians is published in 1928: Berlin's Lesbian Women. The author Ruth-Margarete Roellig describes 12 venues in it, all of which are located in the lesbian hotspot of Schöneberg. This includes the popular café and bar for dancing and entertainment, Dorian Gray.

The Dorian Gray opened at Bülowstrasse 57 in 1921. Every evening, there is a stage programme or live music to dance to, along with carnival costume balls and literary readings. The highlight of the weekend is the variety shows and performances by famous stars of the scene, including the dancer Ilonka Stoyka. Her portrait was even printed on the cover of the lesbian magazine Liebende Frauen (Loving Women).

At the end of the 1920s, the British author Christopher Isherwood arrives in Berlin to sample the pleasures of its liberal gay nightlife. His Berlin Stories were written during his time in Berlin, and would later provide the inspiration for the musical Cabaret. Another icon of queer life in Berlin in the 1920s is the singer Claire Waldoff, who also lived in Berlin with her female partner.

1931

Berlin's legendary Eldorado is an international tourist magnet. Having opened in Kantstrasse in 1924, it relocated to Lutherstrasse in 1927 before moving on to the building on the corner of Motzstrasse and Kalckreuthstrasse in 1931. Mind-bogglingly beautiful female impersonators are the main attraction at the dance parties held every evening. Together with barkeeper Daisy, they become the wildly popular hallmark of the Eldorado, helping it to achieve fame far beyond the borders of Berlin and Germany.

When a conservative and reactionary turning point in government policy first starts threatening the venues with bans in 1932, the proprietor of Eldorado also closes down his dance hall and cabaret. He abandons it to the increasingly influential Berlin SA, which uses it for its electoral campaigns.

1933

Following the seizure of power by the National Socialists and conservatives, a campaign is launched against alleged “public immorality” under a new policy of “national moral renewal”. In May 1933, Hirschfeld's Institute for Sexology is closed and plundered. The new police director in Berlin had already had 14 of the most famous gay and lesbian venues closed in March. Local police departments pass further prohibitions in the city's urban districts. The gay and lesbian associations also feel coerced into abandoning their efforts.

The owners of the all-night bar for lesbians, Mai & Igel, are also affected by the forced closures, while the carnival costume balls for gays and lesbians held at the In den Zelten amusement strip in Berlin's Tiergarten, which were also hugely popular among heterosexuals, are banned with immediate effect. The artists' bar Chez Eugen, known as Moses, feels the full force of the ban: thugs from the SA raid the bar and drive its Jewish owner into exile.

1934-1945

lesbians. There are still a number of bars, camouflaged as artists' bars, to visit, and despite police surveillance, raids and bans, new bars still open up, allowing brief moments of freedom to be enjoyed.

Homosexual men are particularly affected by persecution. Following raids by the Gestapo, the first prisoners are sent to concentration camps from 1934 on. With the tightening of the anti-homosexual laws in 1935, the number of convictions has tripled by 1939. They result in the loss of friends, freedom, wealth and profession, and lead to marginalisation and social ostracism, ultimately making intimate life a source of trauma. Only a small number of those persecuted survive the increasingly frequent deportations to concentration camps occurring during the war. So far, the names of around 400 Berlin men who fell victim to the terror against homosexuals have been identified.

1946

Rising from the ashes and defying the post-war austerity, gays and lesbians re-emerge, holding their first balls again in the midst of the rubble of the destroyed city from 1946 onwards. The organisers are flamboyant female impersonators with names like Mamita, Ramona and Cherie Hell. In 1949, there are more than 20 bars open again to cater to men and 15 for women. They offer a sanctuary and a place to socialise, and they encourage their customers to dream of a better life and fight for new freedoms. Many still have compelling memories of Berlin in the 1920s, yet are also traumatised by their experiences of persecution during the Nazi era.

So too is a legend reborn in 1947, with the transvestite bar Eldorado reopening and remaining open until the end of the 1960s.

1950

A Berlin-based group from the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee was founded in 1949 to resume the efforts made by the first gay and lesbian movement. In 1950, the association was registered under its new name as the Berlin Society for the Reform of Sexual Law. It is part of a homophile movement becoming established across Germany. In Berlin, an Association of Friends was founded in 1952, and a new Association for Human Rights was established in 1958, in which Lotte Hahm – the Berlin woman who fronted the lesbian emancipation movement during the Weimar Republic – was also an active member.

While women are involved in establishing homophile associations, they are also a minority. They meet privately and in women's bars, such as Ida Fürstenau in Kreuzberg, or in Gerda Kelch's Cabaret in Schöneberg, with a venue called Bei Kathi und Eva opening in a laundrette in Schöneberg in 1958.

1960

Venues for gays and lesbians are once again threatened by police raids from the mid-1950s on. Many men once again become the victim of state prosecution under the law against homosexuals, a Nazi law that remains on the books and has since been tightened. When the Berlin Wall is built in 1961, the divided city of Berlin loses its leading role, and its appeal, as the city of freedom for gays and lesbians for a decade to come.

While the gay and lesbian associations disband, the bar scene in West Berlin stands its ground. The number of bars increases, and by 1966 there are 28 different venues. Men continue to meet in Elli's Bier-Bar, or go dancing in Kleist Casino or Trocadero. Chez Nous becomes an attraction in Berlin with its travesty shows. In 1963, Christel Rieseberg opens Club 10 together with her girlfriend in Schöneberg, which acquired prominence as Club de la femme and Dinelo. An intimate club and bar called Inconnu opens in Charlottenburg in 1966.

1970s

A new generation with a new urge for freedom loudly demands to be heard. As so-called Rosa Radikale (pink radicals), they reinvent homosexuality, understanding it as a political and anti-capitalistic promise of liberation. Rosa von Praunheim's film, It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives (1971) inspires the gay scene to establish new associations. This is the launching pad of the gay and lesbian movement.

Homosexuelle Aktion Westberlin is founded in Berlin in 1971, from which the feminist awakening emerges in 1975 with the founding of the Lesbian Aktionszentrum – along with the lesbian archive Spinnboden as an initiative for the discovery, and preservation, of female love. The gay bookshop Prinz Eisenherz opens in 1978. The first Gay Pride Parade/CSD is held in 1979.

A new awakening is being ventured in East Berlin as well: the Homosexuals' Interest Group is founded in 1973. One year later, the transvestite Charlotte von Mahlsdorf opens a venue for gays and lesbians that will later become legendary in her museum dedicated to artefacts from the late 19th century.

1980s

The Schwule Museum (Gay Museum) opens in 1985, followed by Begine, a women's bar and alternative project. Both remain self-administered venues today. While autonomous and free spaces are coming into being, other initiatives are promoting integration. They are active in trade unions, political parties and churches. Choirs, sports associations and hiking groups add diversity and vibrancy to the scene in Berlin.

Berlin Aids-Hilfe is formed in 1985, and benefits from widespread support and becomes a new actor in the gay movement. In 1993, an opera gala at the Deutsche Oper marks the beginning of one of the most successful fund-raising events for Aids-Hilfe.

In East Berlin, gays and lesbians are able to emancipate themselves from 1983 on with the protection of the Protestant Church. In 1986, away from the church, the Sonntagsclub (Sunday Club) opens as a cultural space. It still exists today.

1990s

On the same evening as East Germany's first gay-themed feature film Coming Out celebrates its première, the Berlin Wall falls: it's 9 November 1989.

The CSD parades become more and more colourful and diverse, and much larger, in the reunited capital, and a high-spirited party accompanies the list of political demands being called for. The Transgeniale CSD is held from 1997 to 2016, an alternative event typical to Berlin at which a focus is directed at the political opposition.

In 1997, Berlin celebrates 100 years of the gay movement with an exhibition in the Akademie der Künste (Academy of Arts). Although the lesbian movement is largely neglected by this exhibition, no public protests occur (yet).

A gay-lesbian reunification occurs in 1999: the gay and lesbian association is formed and tries out a new era of cooperation.

2000

The controversial discussion around same-sex marriage, which first started in 1992, becomes the topic of public debate in 1999. In 2001, it results in a registered partnership, before the right to marry is finally extended to same-sex couples in 2017. A run on Berlin's registry offices begins.

By adopting the colours of the rainbow and the word queer, new homopolitical alliances are being formed. Queer becomes a political agenda, and a new label for the LGBTIQ+ movement. Rainbow flags are part of the urban landscape, fluttering in front of the community's businesses and venues, and flying proudly from the town halls in Berlin on the occasion of the annual CSD parade.

The initiative “Berlin supports self-determination and acceptance of sexual diversity” is launched in 2009, showing the Berlin state government's support for diversity and equality of Germany's largest LGBTIQ community.

2017

There are now 150 venues where events are held for the LGBTIQ community: cafés, restaurants, bars and a club scene that is unique in Germany. The range of services, shops, associations and entertainment fills a business directory of its own, which includes more than 1,000 addresses.

On 30 June, Federal Parliament enacts a draft law by the Federal Council that allows same-sex couples to marry.

In September 2017, a monument to the world's first gay and lesbian emancipation movement, which was initiated by the gay and lesbian association, is unveiled on Magnus-Hirschfeld-Ufer, behind the Federal Chancellery. It is formed by six towering, colourful calla lilies – a plant that features both female and male flowers. It is a symbol of the diversity of sexuality and gender, and a metaphor for a confident, flourishing scene – a landscape that was first conceived of, put to the test, and made possible in the 1920s – when Berlin was a role model for an international gay and lesbian capital in which all queer people could find a haven and refuge.

On 1 October 2017 – a Sunday – the first gay and lesbian couples marry in Germany, including Volker Beck, a politician for the Green party, who marries his spouse in Berlin-Kreuzberg after a long fight to be able to say “I do”.