This exhibition takes us right into the world of artists in the GDR, between the stage, the public and the state. It shows photographs that are more than documents: they tell of splendour and contradiction, of joy and confinement, of individual freedom in the field of tension of a political order that simultaneously promoted, controlled and instrumentalized art for its own purposes.

The focus is on the work of Maja Lopatta, born in Wroclaw in 1928. She was editor-in-chief of "Unterhaltungskunst - Zeitschrift für Bühne, Podium und Manege" for many years.

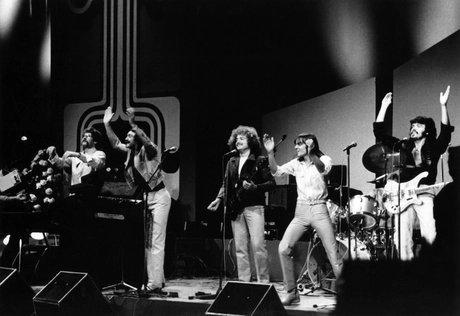

As a journalist, photographer and chronicler, she experienced the GDR cultural scene at close quarters. Her pictures show stars such as Ute Freudenberg, Reinhard Lakomy and Jiri Korn and bands such as Karussel, Puhdys, City and Karat.

But her photographs are more than portraits of celebrities: They reveal the atmosphere of an era that was full of contrasts. A quiet form of resistance always shimmers between the exhilarating lightness, glamorous performances and subversive overtones: the insistence on artistic expressiveness and personal attitude.

Lopatta herself embodied this spirit. She wrote and photographed not to be reflected in the glamor of others, but to capture the power of art. In her recently published autobiography "Life is a Gift", she does not appear as a companion of famous names, but as an independent, lively personality.

Loppata's photographs are complemented by works by Volkhard Kühl and Marion Klemp. Kühl photographed everyday life in East Berlin with a documentary eye, but his passion was for jazz, which embodies freedom in its very idea.

Marion Klemp, on the other hand, offers a multi-layered view of everyday culture in the GDR with her archive, from the Deutsches Schauspielhaus to accompanying Herman van Veen on one of his tours through the GDR. Together, their works open up new perspectives: they show the diversity of artistic forms of expression that found a place in everyday life in the GDR and at the same time were always under the observation of a state that also exercised its control over culture. It is precisely in this field of tension that photography becomes a double testimony: as an image of artistic movement and as a silent document of a political reality.